The Human Rights Act 1998

The Lord Chancellor introduced the Human Rights Bill 1998 into Parliament on 23 October 1997. It incorporates into domestic law the rights and liberties enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights, a treaty to which the United Kingdom is signatory but which until 2000 had no application in domestic law. The Act received Royal Assent on 9 November 1998 and came into force in October 2000.

The Act applies to Dover District Council as they are a public authority. It makes it unlawful for them to violate the rights contained in the European Convention on Human Rights. DDC pays lip service to the Act, but does not heed it in practice.

Any person who is a victim of a violation can use the Human Rights Act.

A victim includes anyone directly affected by the actions, or the inactions, of the public authority. Where there has been a breach of the European Convention on Human Rights, or even where there is about to be, the victim can take proceedings in court under the Human Rights Act. They may be able to take judicial review proceedings, obtain an injunction to stop the violation, force the public authority to take action or obtain damages and compensation.

Although the Human Rights Act 1998 incorporated the European Convention on Human Rights into domestic law, it is still possible to take cases to Europe.

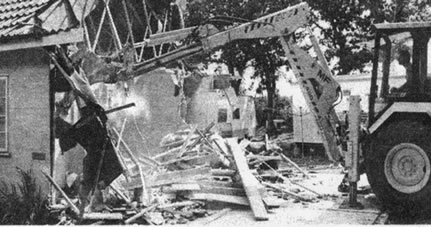

Note: Before the incorporation of the Convention, individuals in the United Kingdom could only complain of unlawful interference with their Convention rights by lodging a petition with the European Commission of Human Rights in Strasbourg. The events surrounding Dover District Council’s unlawful destruction of our bungalow were prior to the Human Rights Act 1998, but their action did come under the jurisdiction of the European Convention on Human Rights (although at the time I was not aware of this). However, the Council’s Legal Department were aware of my rights and their own obligations, but chose to ignore them.

The Human Rights Act 1998 ensures observance of the principle of peaceful enjoyment of possessions and denies the Council any right to deprive a person of their possessions except in accordance with law.

The Human Rights Act introduces an obligation on Dover District Council to act consistently with the European Convention on Human Rights. It is evident that Dover District Council’s continuing actions are disproportionate and violate Article 8 of the Convention.

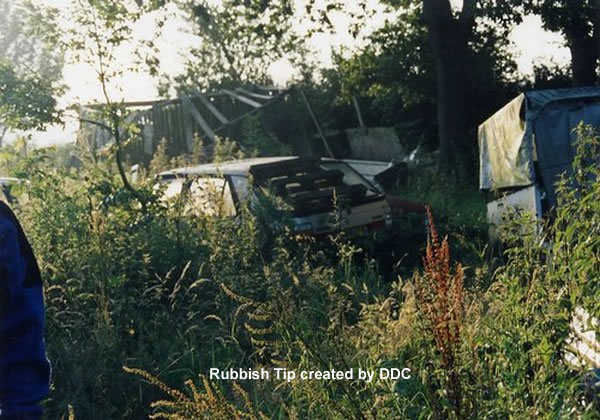

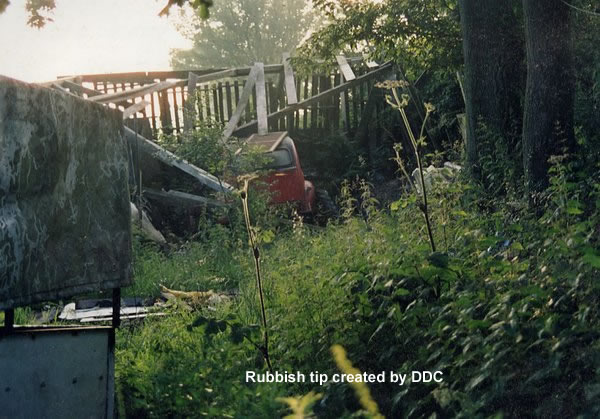

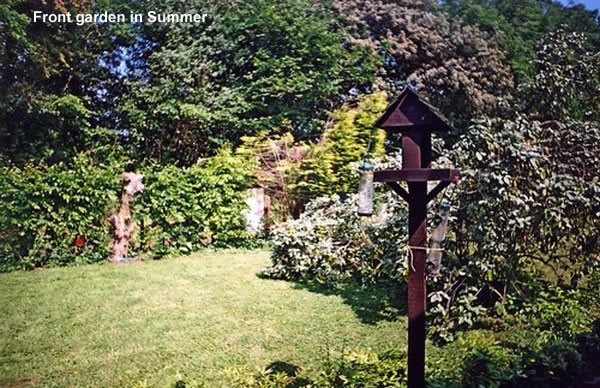

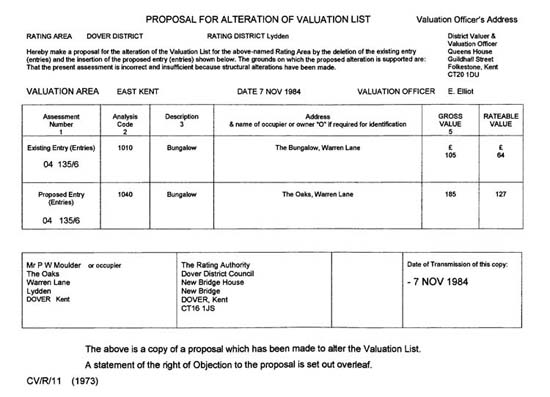

I had a long-standing property right with which Dover District Council interfered and its interference was both unlawful and disproportionate.

Public authorities, which include local planning authorities by definition, are prohibited from acting in a way, which is incompatible with any of the human rights described by the Convention, Section 6(1), unless legislation makes this unavoidable.

6. Acts of public authorities

(1) It is unlawful for a public authority to act in a way which is incompatible with a convention right. If an authority acts in a way, which is incompatible, then separate proceedings can be brought against it under Section 7(1).

7. Proceedings

(1) A person who claims that a public authority has acted (or proposes to act) in a way which is made unlawful by section 6(1) may:

(a) bring proceedings against the authority under this Act in the appropriate court or tribunal, or

(b) rely on the Convention right or rights concerned in any legal proceedings,

Therefore the Act creates rights of action and grounds of appeal whether civil or criminal by a ‘victim’ of the unlawful act. Dover District Council’s Protocol for Good Practice in Planning Procedures 2003 says it aims to ensure and to demonstrate that it takes its planning decisions openly and impartially and for sound, justifiable planning reasons. (None of which appear to have been the case in my situation) The same protocol quotes the Human Rights Act 1998 Article 6 which is concerned with…and I quote from the council’s own web site:

“Guaranteeing procedural fairness in the determination of civil rights and obligations, especially entitlement to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an impartial and independent tribunal. These principles are at the heart of the planning system. Should any councillors, staff or public have any queries about the operation of the Protocol, they should contact the chief planning and building control officer or the monitoring officer.”

However, in my particular case the opposite is true, because they have not taken their decisions openly but often held meetings in secret. This has resulted in unilateral decisions being made because I have not been given the opportunity to put my side of the case. Consequently I have not received a fair hearing as required by Article 6.

Nor have the Council acted impartially but rather they have acted with blatant bias and their own Professional Standards Investigator has confirmed this. In his report he concluded that the Council’s planning and enforcement reports were written in a style that presented them in a very favourable light and in so doing presented me as being troublesome with my various applications and appeals as having no, or limited, merit. The Investigator recorded this as maladministration.

The Investigator also expressed concern that the planning departments conclusions reached since 1984 were based on assumptions that were not sufficiently tested and that contemporary evidence supporting residential use was ignored or glossed over.

In section 6.10 of his findings the Professional Standards Investigator stated:

“After careful consideration of all the files and documents relating to the history of this site I have come to the conclusion that the Planning Committee reached the decision to demolish the complainant’s home based on inaccurate and misleading advice”.

He added at 6.11

“This was maladministration.”

The Human Rights Act 1998, and in particular Article 6, is concerned with guaranteeing procedural fairness in the determination of civil rights and obligations, especially the entitlement to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal. The Act puts the rights of the individual first, on the basis that the rights of the individual are paramount unless there is justification in the public interest.

Primarily it is Article 8, Article 6 and Article 1 of the First Protocol that impact on most planning situations.

ARTICLE 8: Right to Respect for Private and Family Life.

Article 8 guarantees the substantive right of respect for a person’s home.

Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

ARTICLE 6: The Right to a Fair Trial.

Article 6 relates entirely to procedure and it applies wherever there is a determination of a person’s ‘civil rights’. These rights encompass property rights, thus affecting planning law. Article 6 gives everyone the right to a fair hearing, both criminal and civil. This not only means in the courts but also in tribunals, inquiries and administrative decision making of a semi judicial nature, which includes the planning decision making processes.

ARTICLE 1 of the First Protocol: Protection of Property.

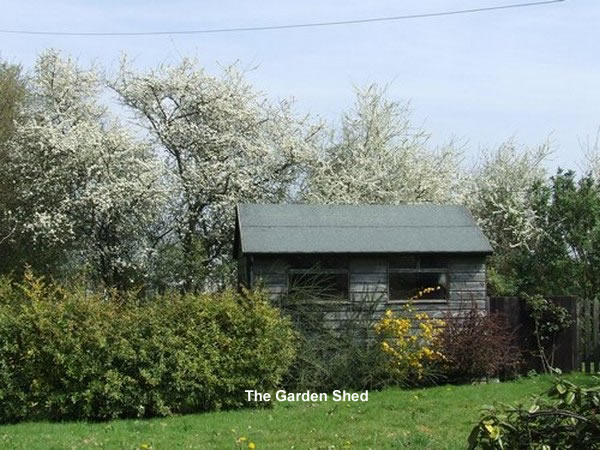

This guarantees a person the right of peaceful enjoyment of their possessions, which includes their home and other land. In my case the Council are denying that right and this amounts to an interference of that right.

The Act states: Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of their possessions. No one shall be deprived of their possessions except in the public interest and subject to the conditions provided for by law and by the general principles of international law.

The Court has consistently held that the terms ‘law’ or ‘lawful’ in the Convention do not merely refer back to domestic law but also relate to the quality of the law, requiring it to be compatible with the rule of the law.

In many cases there is likely to be a significant overlap between Article 8 and the First Protocol, Article 1. However, this right is wider than Article 8 in the sense that it applies to the peaceful enjoyment of all of a person’s possessions and not merely to his home. This could include land, curtilage property, fixtures and fittings.

In simple terms the Act requires that a person’s interests be balanced against the interests of the community. This is something that is supposed to happen with the present planning system, in particular the reports to Planning Committees, but more often than not failing. Committee members should specifically bear human rights issues in mind when reaching decisions on all planning applications and enforcement action (but they don’t!).

In considering the application of Article 8 a 5-stage test can be applied:

- Does a right protected by Article 8 apply?

- Has an interference with that right taken place?

- Is the interference in accordance with the law i.e. is there a legal authorisation for the interference?

- Does the interference pursue a legitimate aim?

- Is the interference necessary in a democratic society?

The fourth stage of the test: Does the interference pursue a legitimate aim?

The legitimate aims are listed in Article 8(2) and they are:

- National Security

- Public Safety

- Economic Well Being of the Country

- The Prevention of Disorder or Crime

- The Protection of Health or Morals

- The Protection of the Rights and Freedoms of Others.

A decision made by a public authority must not be irrational, or ‘unreasonable’ and many years ago a test, commonly called the “Wednesbury test”, was formulated for the purpose of determining whether a public authority had acted outside its statutory powers.

A decision is ‘Wednesbury Unreasonable’ if it is:

“so unreasonable that no reasonable authority could ever have come to it”.

The test derived from: Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] and was defined by Lord Greene as:

“so unreasonable no reasonable body could have come to the decision”.

Lord Diplock gave a vivid explanation of ‘Wednesbury unreasonableness’ in Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service [1985] when he stated:

“Wednesbury applies to a decision which is so outrageous in its defiance of logic or of accepted moral standards that no sensible person who had applied his mind to the question to be decided could have arrived at it”.

What is ‘unreasonable’ will depend on the circumstances of the case. As a general rule a decision will be unreasonable if it goes:

“beyond the range of responses open to a reasonable decision maker”. R v Ministry of Defence, ex p Smith [1996]

Proportionality. The Human Rights Act 1998 has added a new dimension to local authorities decision-making and a tougher test than the test of reasonableness – one of ‘proportionality’ – looks at whether the action is proportionate to its aim. If a local authority’s decision interferes with human rights then the courts generally require stronger proof that the decision was reasonable.

Government guidance states that when taking enforcement action, the issue of proportionality must be at the fore of all decision making, as such action will by definition regulate the way in which an individual uses, develops or occupies his land, and may well affect his home and personal life, offending Article 8 and the First Protocol.

Proportionality means that the action taken must lead to the minimum interference with those rights that is necessary to achieve the authority’s wider aims. In other words, to reformulate a test that has been at the heart of government guidance on enforcement for many years, the action taken must be commensurate with the seriousness of the breach.

Deprivation of property. The European Convention has regarded the payment of compensation, or the lack of it, as an important feature in deciding whether the action of the State was proportionate or not. The lack of compensation will lead more easily to a conclusion that there was a lack of proportionality. This will be especially relevant in cases of deprivation of property.

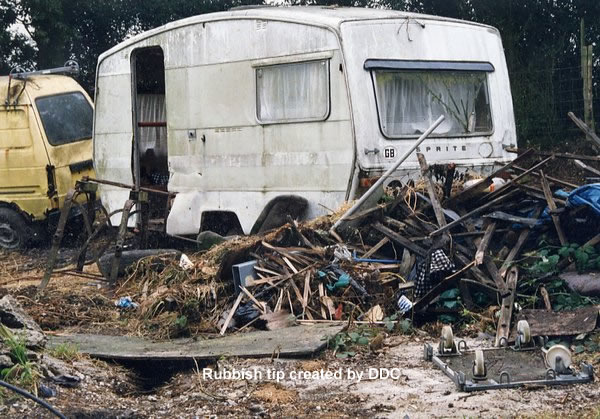

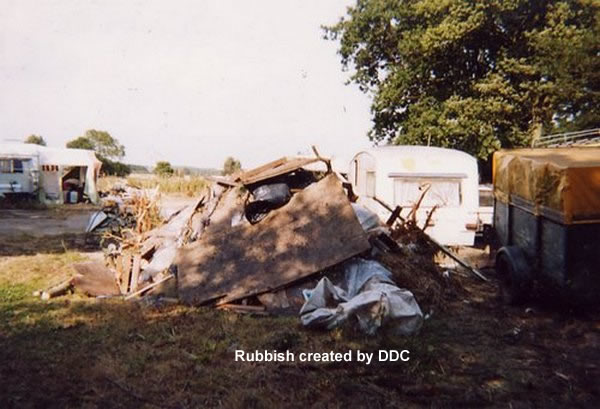

I fully recognise and respect the need for planning control in the countryside but disproportionate enforcement action should never have been used to wage a personal vendetta against me because of a technical breach of the planning regulations, which was all that occurred when I carried out works of improvement to my bungalow.

However, I was never allowed the opportunity to remedy the technical breach and Dover District Council went far beyond what was necessary to satisfy planning policy.

Procedural Impropriety. The process whereby a decision is made by a public authority must not be undermined by ‘procedural impropriety’ and this includes a failure to follow procedural rules, a failure to observe the rules of “natural justice” or to act fairly towards someone.

Lord Justice Muskill, Greater London Council (1985) identified four ways in which a decision might be procedurally improper, namely:

- Unfair behaviour towards persons affected by the decision.

- Failure to follow a procedure laid down by legislation.

- Failure properly to marshall the evidence on which the decision should be based. For example, taking into account an immaterial factor or failing to take into account a material factor or failing to take reasonable steps to obtain the relevant information.

- Failure to approach the decision in the right spirit, for example, where the decision maker is actuated by bias or where he is content to let the decision be made by chance.

Home

Nadeem Aziz, Dover District Council’s Chief Executive, commissioned an investigation into my case and appointed his Chief Investigator, to carry it out. After a thorough investigation, which took many months to complete, Mr Aziz was presented with independent evidence, which was obtained from the Council’s own working papers and files, and from interviews with employed officers.

Nadeem Aziz, Dover District Council’s Chief Executive, commissioned an investigation into my case and appointed his Chief Investigator, to carry it out. After a thorough investigation, which took many months to complete, Mr Aziz was presented with independent evidence, which was obtained from the Council’s own working papers and files, and from interviews with employed officers. Dover District Council officers are guilty of Misfeasance in Public Office and it is scandalous that Nadeem Aziz, who seems to have no concept of natural justice, has taken no action against them. In any other organisation the individuals responsible would be suspended, or at least relieved of their responsibilities pending a thorough investigation. Mr Aziz’s neglect to suspend officials with serious allegations against them is a disgrace and his failure to mount a wider investigation raises even more disturbing questions. The fact that he spent months trying to bury or ignore the findings of an investigation that he personally commissioned, and which cost the local taxpayer many thousands of pounds, also raises serious questions about his motivation to cover-up this issue. It may have something to do with the fact that before his internal promotion to Chief Executive he was in charge of the planning department that failed in its duty of care to correct the clear violations in law perpetrated by the very department which he previously controlled.

Dover District Council officers are guilty of Misfeasance in Public Office and it is scandalous that Nadeem Aziz, who seems to have no concept of natural justice, has taken no action against them. In any other organisation the individuals responsible would be suspended, or at least relieved of their responsibilities pending a thorough investigation. Mr Aziz’s neglect to suspend officials with serious allegations against them is a disgrace and his failure to mount a wider investigation raises even more disturbing questions. The fact that he spent months trying to bury or ignore the findings of an investigation that he personally commissioned, and which cost the local taxpayer many thousands of pounds, also raises serious questions about his motivation to cover-up this issue. It may have something to do with the fact that before his internal promotion to Chief Executive he was in charge of the planning department that failed in its duty of care to correct the clear violations in law perpetrated by the very department which he previously controlled.