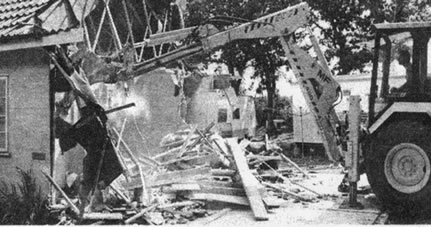

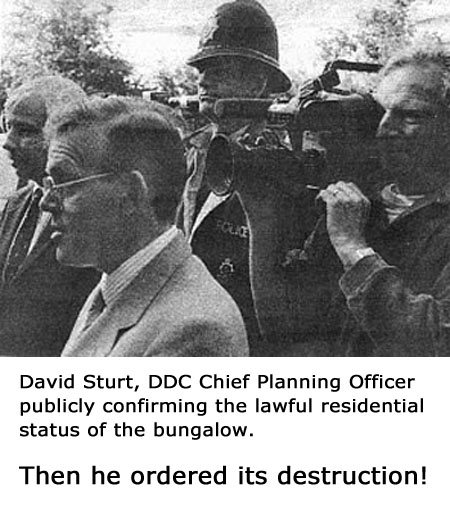

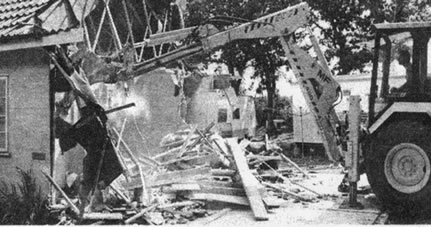

The original action taken by Dover District Council, when they destroyed my bungalow in 1989, was unlawful and therefore it follows that every action that the Council has taken against me since, is also unlawful.

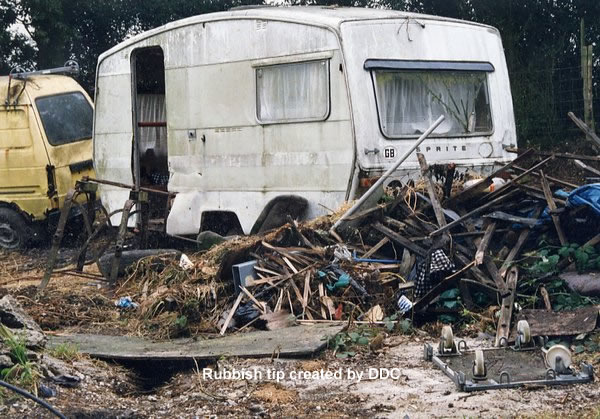

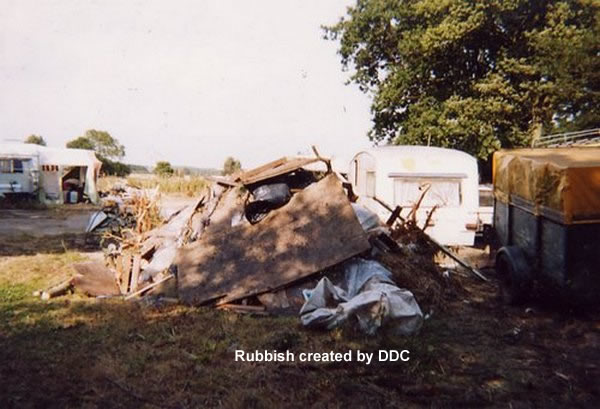

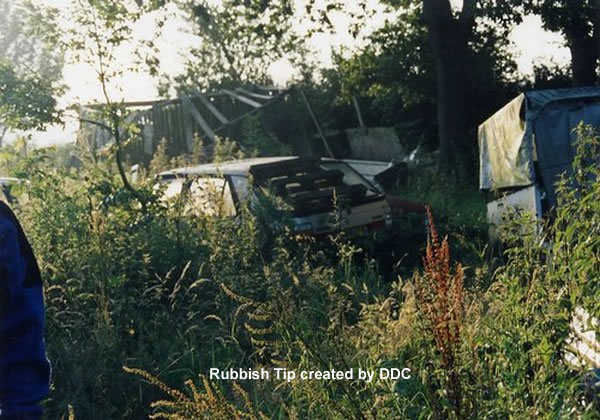

Before Dover District Council destroyed my bungalow I placed a caravan in the garden adjacent to it, which my daughter lived in initially, joined by the rest of the family after the bungalow had been destroyed. The caravan had therefore been legally sited before the bungalow was demolished and, as its use was ancillary to the primary use of the land i.e. residential, the lawful residential use of the land continued uninterrupted.

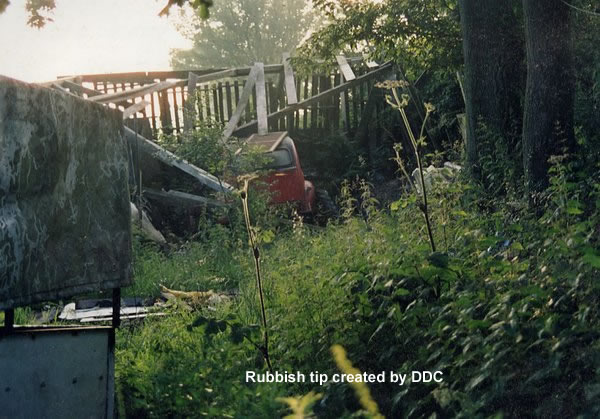

A fact evidenced by this copy of a newspaper cutting which shows the Council destroying the bungalow. The caravan can be seen behind the JCB.

Subsequently the Council unlawfully issued an enforcement notice on the 27 February 1990, ordering its removal.

In a Committee Report, dated 7 Sept 1989, DDC reported that when they demolished my bungalow they noticed a mobile home was stationed in my garden. In their report the Council falsely stated:

“Such use of the land also required planning permission, which had not been obtained”.

But the mobile home did not require planning permission, and the Council took unlawful action against me, despite its own legal department providing the following advice in a memo dated 22 August 1989:

“A mobile home/caravan with wheels is not a structure and therefore the placing of such items on land cannot constitute operational development. Operational development required planning permission regardless of the use intended to be made of the land or the building intended to be constructed. It follows that planning control of the placing of a mobile home/caravan on land depends solely upon establishing that a material change of use has occurred.#It is arguable that existing residential use rights have existed on the site since pre-1963 and have continued since the end of 1963 and that the demolition of the rebuilt structure does not evidence an abandonment of those use rights. An EN may therefore be challenged on the ground that the caravan is being used for residential purposes, and this does not constitute a material change of use by reason that the site has the benefit of existing residential use rights.”

The Council’s legal department had therefore informed Committee, unequivocally, that they could only take action against me if there had been a material change of use. Clearly there had been no change of use because the mobile home was being used for residential purposes and the site benefited from existing residential use rights.

Yet, despite taking legal advice, the Council still went ahead and unlawfully took action to remove my mobile home.

It was held by the Court of Appeal (Wealden DC v S of S 1987) that the stationing of a caravan on land did not of itself establish a material change of use. The Notice must also state the use to which the caravan is put. If that use is ancillary or incidental to the primary use of the land, then no change of use occurs at all…

The use of the mobile home certainly was ancillary or incidental to the primary use of the land, i.e. residential, because that became home for my wife, myself and our two children just prior to DDC destroying our bungalow.

Another ruling that clearly supports my case is: Restormel Borough Council -v- Secretary of State for the Environment and Rabey [1982] JPL 785

In essence, a hotel placed a caravan within its grounds to house its waitresses. The council served an enforcement notice.

The Court held that there had been no material change of use. The use of the caravan was incidental to the main use of the land. The test was to be applied by looking at the alleged change in the context of the entire planning unit.

Therefore, in my case, planning permission was not required and an enforcement notice should never have been served.

Clearly and without doubt there had been no change of use whatsoever and there is irrefutable evidence proving that the property had been used continuously as a lawful residence since 1928.

Further evidence of the long-standing lawful residential use of my property is contained in a report from the Council’s own Professional Standards Investigator when he stated in section 3.32:

“Taking into account the Planning Inspectors findings in November 2000, the Head of Legal Services advice to the complainant’s solicitor in her letter of 8th October 1984, the evidence provided by the next door neighbours and the undisputed evidence that between June 25th 1984 and 31st July 1989 the complainant and his family lived at the Oaks, it is my view that there is a record of residential use of the site from 1928 to 31st July 1989”.

The Professional Standards Investigator also recorded, in his report, the names of all previous residents who had occupied the property from 1934 until the time I purchased it in 1984. He also confirmed that there are letters on file from other local residents confirming residential use during the period in question.

Further evidence that the residential use had not ceased was contained in a letter dated 8th October 1984 from Lesley Cumberland, Director of Legal and Administrative Services in which she stated:

…”I have conferred with the Director of Planning on the alleged statement that the residential use of the site may have ended, and I can confirm that the Council are not saying that the residential user rights have been abandoned, only that the operation carried out on site is, as a matter of fact and degree, a building operation and thereby constitutes development requiring planning permission”…

The Council’s legal department also advised Committee of the following:

“It is almost certain that if an appeal is lodged against an EN (enforcement notice) alleging that a material change of use has occurred, this will necessitate a thorough investigation by Officers of the history of the use of the site for residential purposes”.

The question has to be asked:

Why didn’t the Council carry out an investigation to confirm the long-standing residential use of my property before they demolished my home?

Their philosophy is clearly, ‘knock it down first and ask questions after’.

Since this dispute started in 1984 Dover District Council has repeatedly presented inaccurate and misleading information. This is confirmed in the findings of the Council’s Professional Standards Investigator who stated in his report:

6.10 “After careful consideration of all the files and documents relating to the history of this site I have come to the conclusion that the Planning Committee reached the decision to demolish the complainant’s home based on inaccurate and misleading advice”.

6.11 “This was maladministration”.

The Council also falsely stated that I had erected a new bungalow. That is not the case, I did not erect a new bungalow but I did renovate the existing bungalow. However, the demolition of a building does not in itself destroy existing use rights formerly enjoyed with it.

In Jennings Motors v Secretary of State [1982] the landowners had demolished a building and erected a new building on a small part of the entire site, but without obtaining planning permission. The local authority argued that this was a change of use and a breach of planning control.

The Court disagreed and ruled that the erection of a new building to replace an earlier one did not constitute a new planning unit, but the new building could inherit the use established by the former.

The motives of Dover District Council are extremely questionable in this case for it’s certainly not their remit to punish any individual for an alleged breach of planning control.

The remedy for any unauthorised development is provided for within the Town & Country Planning Act, which is very clear and precise on the matter.

The relevant Act in this particular instance was:

The Town & Country Planning Act 1971 c.78 Part V section 87

(6) An enforcement notice shall specify—

(b) the steps required by the authority to be taken in order to remedy the breach, that is to say steps for the purpose of restoring the land to its condition before the development took place ….

If a precedent had been set since the 1971 Act then the 1990 Act would have been amended but that is not the case. The relevant 1990 Act states:

Town & The Country Planning Act 1990 c.8 Part VII section 173#(3) In this section “steps to be taken in order to remedy the breach” means steps for the purpose – (a) of restoring the land to its condition before the development took place…

The Council never allowed me the opportunity to carry out the steps stipulated by the Town and Country Planning Act and this is confirmed by the Council’s Professional Standards Investigator who stated that there is no record in the files to show that I was given the opportunity to put matters right.

There is compelling evidence that the Council’s action was wrong in law and therefore the enforcement notice should never have been served.

Home

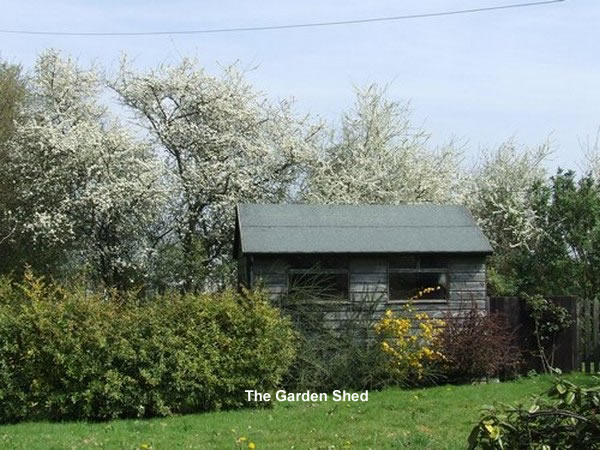

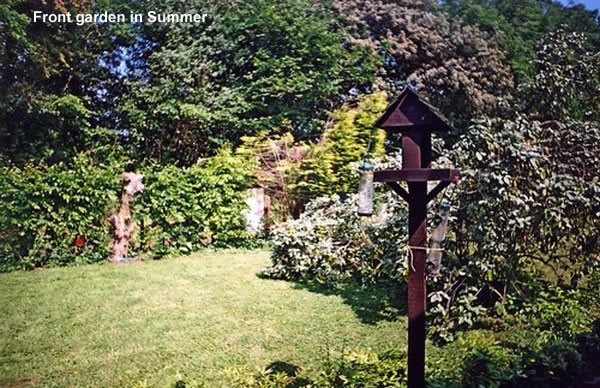

A few days before Christmas, 2008, four representatives from Dover District Council DDC visited me at my home. Their manner was aggressive and intimidating when they made it absolutely clear that the purpose of their visit was to put in place arrangements for the complete destruction and removal of my home, garden shed and greenhouse.

A few days before Christmas, 2008, four representatives from Dover District Council DDC visited me at my home. Their manner was aggressive and intimidating when they made it absolutely clear that the purpose of their visit was to put in place arrangements for the complete destruction and removal of my home, garden shed and greenhouse.