The English Oak or Pedunculate Oak (Quercus) has always been seen as the national tree of England and its great height, age and strength have made it the king of the English forest and a symbol of endurance. The Oak has been recorded in British history since the interglacial periods, around 300,000 years ago! It was the most common tree in our forests about 5,000 years ago and still is today.

The mighty English Oak is embedded into the history and folklore of England. It is highly valued for its strength and durability and has always been used in the construction of furniture and houses. For very many years, and up until the middle of the 19th century, the English oak was used to construct ships for the Royal Navy. During that period there were eight warships called HMS Royal Oak.

It is probably the best-known native tree and although found in mixed woodland throughout the UK and on many of the British lowlands, it is most common in the South and East. It’s an important feature of the English landscape, renowned for its longevity and noted for its distinctive leaves and groups of acorns.

It is probably the best-known native tree and although found in mixed woodland throughout the UK and on many of the British lowlands, it is most common in the South and East. It’s an important feature of the English landscape, renowned for its longevity and noted for its distinctive leaves and groups of acorns.

The ‘king of trees’ has a special place in the English psyche, and is a magnificent tree with a broad, irregular crown. The bark is grey and fissured, and develops burrs as it ages. The massive main branches often develop low on the trunk and become twisted and gnarled with age. The leaves have 5-7 pairs of lobes, forming a typical wavy-edged outline; the upper surface is dark green and the underside is paler.

When growing in open areas it has a wide, rounded crown, but woodland specimens are usually tall and slender. It is a deep-rooted tree and can tolerate most soils, except shallow soil, but it prefers moist, mineral rich soils with pH in the range 4.9-5.4. It will put up with being waterlogged for long periods of time and mature trees will tolerate flooding even by seawater.

The branches of the trees are quite irregularly spaced and sized, and suddenly going from being quite thick to twiggy. The twisted furrowed bark is greyish in colour and this thick bark will often save trees from forest fires and if the top is damaged then new shoots will come out from below. The leaves grow on very short stalks and have deep lobes with the pair nearest the base pointing backwards. The acorns form in small clusters on long stalks.

Under sheltered conditions and deep soil, Oaks can reach impressive heights and grow into magnificent trees of 45 metres or more in height but usually its leading shoot is eaten, forcing out side branches to form a large spreading dome up to 20 metres in height.

The tallest trees are not particularly old however, probably no more than about 300 years. The really ancient oaks are not particularly tall as they occur in places that were ancient wood pastures, where widely spaced trees were pollarded for centuries to provide timber and firewood.

The largest Oak recorded was a Newlands Oak and its trunk had a massive girth of 45 feet (13.5 metres) when it fell. Today, the UK’s largest Oak is called the Major Oak, it stands in the heart of Sherwood Forest and according to local folklore it was Robin Hood’s headquarters. It weighs an estimated 23 tons, has a girth of 33 feet and is about 800-1000 years old.

The Oak can live for hundreds of years and has always been important for its timber. The Oak’s sturdy timber is strong and lasts a long time, making it good to build the frames of houses, barns and halls, but it’s also renowned for its use in furniture, gates and in casks used for maturing wines and spirits. The bark is used in the tanning of leather.

In the 18th century, huge Oak timbers were in demand for ships. Trees were specially cultivated and selected for ‘shipwright’ timber with natural curved branches for the ribs of the hull and ‘knees’ to strengthen the joints.

The Oak tree, has a period of quite rapid growth for around 80-120 years and that is followed by a gradual slowing down. By the time the tree is 80 years old, it may well be over 20″ (50cm) in diameter. Acorns are not produced until the tree is about 25-40 years old with seed production reaching a maximum between 80-120 years. After about 250-350 years, the decline of the tree sets in, branches die back and the diameter growth slows right down.

The English Oak is deciduous and loses its leaves usually around November, when they turn yellow, orange and brown before dropping off. Oak leaves rot quickly on the ground, helping to form soil and providing food for other plants to grow.

The tree comes into leaf fairly late, usually in April but often not until mid May. There are male and female flowers on the same tree and the pale green catkin, typically produced in May, is the Oak’s male flower. The less conspicuous, reddish-brown coloured female flowers, are barely noticeable, short spikes near the tip of each twig on the end of long stalks.

The fruit of the oak tree is the acorn and this contains the seed of the tree. The acorns are smooth, shiny, and oval shaped, chestnut brown in colour and up to 40mm long with up to a third of their length sitting in the acorn cup. New acorns may have greenish stripes on them, but these soon disappear. The cups are rough and on stalks that are usually about twice the length of the acorn itself.

The acorns usually appear in September and the tree tends to fruit very abundantly every 4-7 years, whilst in other years, fewer acorns are produced and in some none at all. The egg-shaped acorns sit in scaly cups and develop at the ends of long stalks called ‘peduncles’. It is these stalks that give the tree its alternative name the ‘Pedunculate Oak’.

When acorns loosen in their cups, the oak tree provides an important winter food source for many wild creatures. In ancient times the acorns were a harvest for the wild boar, but now, jays, pigeons, pheasants, ducks, squirrels, mice, badgers, deer and pigs feast on acorns in the autumn.

Because the acorns are taken for food by several different birds and mammals, there is a chance of them being dropped a long distance away. In fact, although acorns fall beneath the Oak tree, because there are so many predators, the odds of them taking root in and around an existing Oak is very slim. It is mainly Jays who are responsible for the resurgence of new oaks as they carry the acorns away, bury them for their winter food store and often forget about them, resulting in an oak tree seedling emerging from the ground.

The acorns that survive being eaten, root very soon after falling and the seedlings develop a substantial tap root, though a shoot is not produced until the spring. The seedlings are fairly tolerant of shade and can survive the loss of some early shoots, however, they are susceptible to other damaging influences such as caterpillar defoliation or attack by the oak mildew fungus (Microspaera Alphitoides).

The acorns that survive being eaten, root very soon after falling and the seedlings develop a substantial tap root, though a shoot is not produced until the spring. The seedlings are fairly tolerant of shade and can survive the loss of some early shoots, however, they are susceptible to other damaging influences such as caterpillar defoliation or attack by the oak mildew fungus (Microspaera Alphitoides).

The mature English Oak tree supports a larger number of different life forms than any other British tree. This includes up to 280 species of insect. Up to 320 taxa (species, sub-species or ecologically distinct varieties) of lichens, growing on the bark of any one tree.

The mature wood is covered in a thick bark that has deep grooves (fissures), which is ideal for all sorts of insects to hide in. The vast array of insect life found in the Oak tree means that of all British trees, it supplies the most food for birds such as Tits and Tree Creepers.

In the winter months a variety of fungi can be seen attached or around the Oak tree. Some of the fungi prefer living wood whereas others prefer the dead wood. An old stump or branch might well have the fairly harmless Sulphur Tuft attached to it and not to be confused with Honey fungus, which is a deadly root killing fungus, of similar colour.

In early spring flightless female moths crawl up the tree to mate and lay their eggs. The eggs hatch in spring coinciding with the young Oak buds opening into leaf. Hundreds of young caterpillars chew on the new leaves; so many in fact that if you stand near an Oak tree you can hear the droppings falling onto the ground below like rain. Later in the season the leaves develop tannin, which acts as a repellent to the caterpillars. Soon, the Moth pupates in the leaf litter below the tree and in the spring the whole cycle starts again.

All the caterpillars chewing away can take its toll and leave the Oak tree leaves holed and distinctly tatty, but the Oak protects itself by producing another crop of leaves in August (referred to as lammas growth – the time when trees harvest their fruits).

The activity in an Oak tree is tremendous owing to sap-sucking bugs and aphids, boring weevils, bark eating beetles, spiders, snails, bark-lice, crickets, earwigs, hornets, lacewings – all of which enjoy the hospitality of the Oak. Around 200 different types of caterpillar alone use the Oak and in doing so provide essential food for a variety of small birds feeding their young in the late spring and summer.

Often, strange structures appear on an oak tree and these attractive round balls seen swinging amongst the catkins or attached to the buds are known as Galls and house different types of wasp larva.

There are various types of gall and they are caused by a gall wasp that lays its eggs inside the acorn, causing it to mutate. These wasps do not usually cause damage to the tree and are nothing to worry about. The most common are the Currant galls, the red Cherry galls and the Marble galls. If you were to cut one of those galls open, you would find the wasp larva curled up inside.

The Oak tree has had more stories told about it than any other tree.

There’s that piece of Irish folklore often used to forecast the weather!

If the oak before the ash,

Then we’ll only have a splash.

If the ash before the oak,

Then we’ll surely have a soak!

The traditional Yule Log used as a Christmas decoration was originally an oak log. It used to be dressed with mistletoe and holly.

People used to carry acorns, as they were believed to bring good luck and to ward off illness.

The Oak tree has been important to lots of different groups of people, including Greeks, Romans, Celts and Druids.

Many meetings and ceremonies have taken place under oak trees, which were thought to be magical.

Roman soldiers often wore crowns of oak leaves when celebrating victory in war.

Home

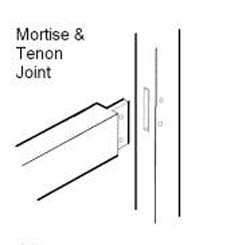

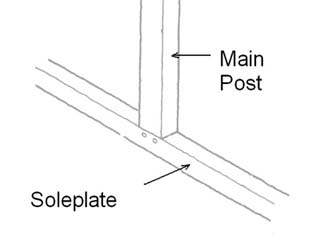

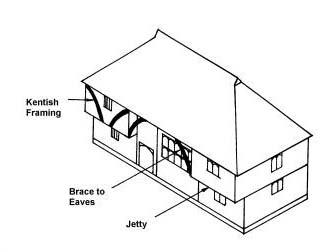

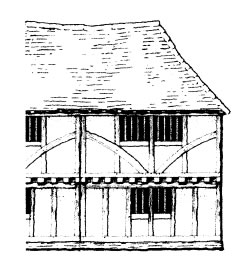

Mortise and tenon joints first became popular in the Middle Ages when a revolution in oak timber-framing took hold but they were used as far back as prehistoric times. The durability of oak and the craftsman’s skill has meant that many of our most treasured historic buildings date from this period.

Mortise and tenon joints first became popular in the Middle Ages when a revolution in oak timber-framing took hold but they were used as far back as prehistoric times. The durability of oak and the craftsman’s skill has meant that many of our most treasured historic buildings date from this period.